Article

7 Tips for Creating a Great Project Plan

A strong product development process requires planning and smart product strategy. Follow these 7 steps to create a successful project plan.

If you’ve ever developed a new product, then at some point, you’ve probably heard management direct the following statement at a cowering project manager:

“This project is off the rails! It’s late and costing way more than you told us it would. You had a detailed project plan. How could this happen?”

Let me count the ways.

A project plan is a tool we use to help us coordinate the people and resources necessary to create and deliver a product to its customers. This plan is an important part of any product development process. Without a plan, it is next to impossible to coordinate the resources necessary to create a successful product.

But why are some plans great and others disasters? How do you go about creating a project strategy that your team can execute successfully?

7 tips you can use to create a great project plan:

Put Reasonable Effort into Planning the Product Development Process

Sometimes, it takes longer to create the plan and get it approved than it does to get through development. Yes, this really happens.

When you create a project plan, set a clear limit on:

- How much time you have to create it

- Who needs to approve it

Done correctly with these imperatives in mind, your project planning won’t necessarily be quick, but it will be efficient. Set your expectations at the onset for what’s reasonable for this project.

Use the Right Level of Detail

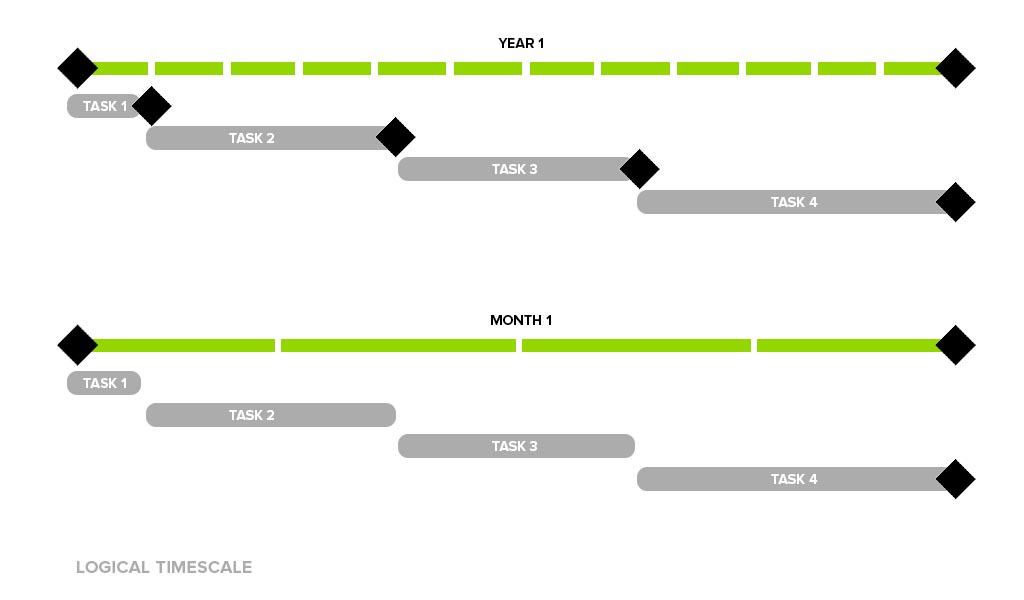

This is tricky to get right in your project plan. But generally speaking, the level of task granularity should be about one logical time-measurement period below the project’s duration. And there should be tasks and milestones defined for the major activities and checkpoints.

For example, if you expect the product development process to take one year, task granularity should be set at the quarter or month level. If your project is a few months long, weeks would be appropriate.

So if your multi-year project plan has daily tasks, there’s a problem. Because unless the project is just a series of repetitive, done-it-before tasks (in which case, it’s probably not a product development project in the first place), there is no way to effectively track and manage this level of detail.

When you see a product strategy that’s laid out this way, it’s usually just a sign of inexperienced project managers and/or management.

The corollary to too much detail is too little detail.

A rational plan needs enough granularity to show how tasks interrelate and result in your important deliverables.

If your plan says, “a month to design, a month to test, and then we’ll build thousands,” it hasn’t been thought through adequately. Make sure you’ve at least identified the major steps in your product development process with rough resource estimates included.

Leave Room to Recover in Your Project Plan

Problems are part of product development. So be ready for them.

The infamous “success-based” plan is a euphemism for “there’s no room for error, so assume everything will go perfectly—or else.”

This never works. Why? Because people are involved, and people make mistakes.

Make sure your plan includes checkpoints where the work is validated and allocates adequate time and resources to make the updates identified during that validation. Along with properly allocated time and resources, any product development process should allow for a series of prototypes and multiple iterations of the design.

This is one of the easiest things you can do to mitigate the potential risk involved in developing something new.

Use Realistic Working Hours

Your plan should include appropriate provisions for non-working time, and it shouldn’t demand excessive overtime in order to succeed.

A good project strategy only uses weekends, holidays, and overtime to recover from unforeseen bumps in the road. People can perform at high levels working 80-hour weeks but only for reasonable durations.

You want the best from your people, so design a product development process that sets them up for success.

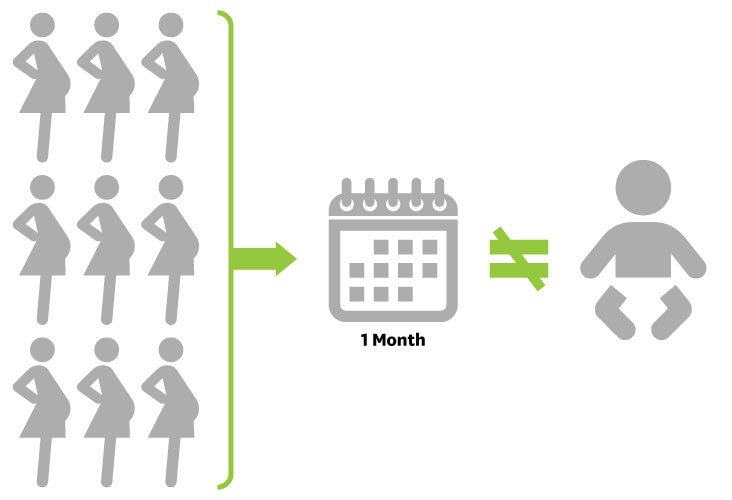

Beware the Mythical Man-Month Rule

Nine women cannot deliver a baby in one month. The same goes for product development. In most cases, you can’t just double the resources to cut a task’s duration in half.

Yes, in many cases, you can and should split up tasks so that multiple people can share the work. But here’s the cost: coordination overhead will increase geometrically with the number of people working together on a task.

Remember that whenever you double up on resources, you also double up on cost, risk, and overhead.

Get Project Development Process Inputs from the Entire Team

You know the game of chicken, right? Two cars, usually driven by male teenagers (or, also stereotypically, older males still acting like teenagers), drive toward each other at high speed, and the first to swerve out of the way loses.

Organizations sometimes do this with their schedule inputs, and it’s a killer for the project strategy and the team.

Here’s a classic example: a software team realizes that a planned six-week task is really going to take 10 weeks, but they don’t tell you or the rest of the team. Instead, they hide their schedule “slip” behind the electrical team, who they believe is going to be at least four weeks late delivering their PCBA. Of course, the electrical team is trying the same tactic in reverse.

This usually happens when the project manager fails to consult one or more of the contributing groups for their input.

Avoid playing schedule chicken. Get planning input from the whole team.

Use Good Estimation Practices in Your Project Strategy

There are many well-documented ways to estimate task effort and duration. The good ones have these principles in common:

- They require that more than one person provide an estimate for the tasks.

- They differentiate between calendar time and effort.

- They require input from all the groups that will participate on the program.

If your technique does not meet these three requirements, you will greatly reduce your chances for a successful project plan.

Summary

Simply put, the project plan is a tool to help us coordinate the people and resources necessary to create and deliver a product to its customers.

Like any other tool, if a project plan is used incorrectly, it can lead to disastrous results.

But when we understand its strengths and weaknesses, and how it should be used, the project plan becomes an invaluable component of your product development process. It helps teams deliver the next great product with high quality and superb value—and (maybe most importantly) do so in a predictable manner.